“The line separating investment and speculation, which is never bright and clear, becomes blurred still further when most market participants have recently enjoyed triumphs. Nothing sedates rationality like large doses of effortless money. After a heady experience of that kind, normally sensible people drift into behavior akin to that of Cinderella at the ball. They know that overstaying the festivities — that is, continuing to speculate in companies that have gigantic valuations relative to the cash they are likely to generate in the future — will eventually bring on pumpkins and mice. But they nevertheless hate to miss a single minute of what is one helluva party. Therefore, the giddy participants all plan to leave just seconds before midnight. There’s a problem, though: They are dancing in a room in which the clocks have no hands.” — Warren Buffett in a letter to shareholders.

The Most Dangerous Idea in Investing

If I were to ask you what you think the most dangerous idea is in investing that investors must be wary of, what would you say that is? Bear markets? High volatility? Technical analysis? No, no, and again no. The most dangerous idea in investing is the following four words: “This time is different”.

“This time is different” is a result of the hubris of an overly eager investor, the rallying cry of investors that believe they can ignore previous attitudes, beliefs, concepts, or ideas about investing because, “This time it’s different”. When you hear say somebody say that phrase, or something like it, you should run as far away as possible and don’t look back. That phrase has caused more money to be lost than at the point of a gun. I don’t care how different the latest investing craze seems, or how widely innovative some piece of technology is that you’re investing in, there is always at least some similarity between today’s investing experience and experiences of the past. In fact, these similarities may be more remarkably closer than you might think.

This still holds true even in the “wild-west” field of investing in cryptocurrency. As much as we’d like this to not be true, fundamentals will still apply for cryptocurrencies in the long-term. Which cryptocurrencies/tokens will provide actual value in 10–15 years? Which tokens are designed in such a way that it actually makes sense to hold the token for a long time? Is the team behind a cryptocurrency/token experienced, reputable, and trustworthy? Is a cryptocurrency/token addressing a real-world problem, or is a token attempting to create a solution for a problem that doesn’t actually exist (i.e. putting the cart before the horse)? You must be able to answer these questions fully if you want to invest in cryptocurrencies/tokens that will provide you with strong returns in the next few years.

It’s understandable, of course, why one might get into the “This time is different” mentality when it comes to cryptocurrency. After all, usually this mentality is correlated with dreams of unimaginable riches, a belief that this time truly is different, and that previous times in which something similar occurred were fundamentally different (e.g. the dot-com bubble)

During the dot-com bubble, investors had the mentality of “This time is different” as well, because of the innovativeness of the technology and its long-lasting implications. During this bubble, many investors were eager to invest in any company at any valuation, that had a “.com” suffix at the end of its title.

We’re seeing the same thing happening today — A British company called “On-line plc” that invests in internet and information businesses announced that it was planning on changing its name to “On-line Blockchain Plc”. Its shares jumped 394% in one day. This isn’t some wild or extreme case either. A biotech company called “Bioptix”changed its name to “Riot Blockchain” and its stock rose more than 50% ahead of the announcement, and 17% after they formally unveiled the name-change.

This is concerning. The fact that a company is able to simply add a term to its name, and have its stock’s value skyrocket, should show you the irrationality that the market has for anything and everything blockchain/cryptocurrency related. It’s no different than the greater fools willing to pay massive valuations for dot-com companies.

Mark Twain once said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes”. In no field is this more true than investing. According to the book This Time Is Different, “The U.S. conceit that its financial and regulatory system could withstand massive capital inflows on a sustained basis… arguably laid the foundations for the global financial crisis of the 2000s.” I’ll let you, the reader, decide whether or not this holds true of the cryptocurrency market as well.

Known Unknowns, Unknown Knowns, and Systemic Risk

“There are known knowns, things we know that we know; and there are known unknowns, things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns, things we do not know we don’t know.” — Donald Rumsfeld. Donald Henry Rumsfeldm, Born: 9 July 1932 (age 86 years [n year 2018), is a retired American political figure and businessman. Rumsfeld served as Secretary of Defense from 1975 to 1977 under Gerald Ford, and again from 2001 to 2006 under George W. Bush.

“There are known knowns, things we know that we know; and there are known unknowns, things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns, things we do not know we don’t know.” — Donald Rumsfeld

If when you hear or see the words “systemic risk”, your eyes glaze over in confusion, then there’s a problem. So I’m going to take the following paragraph to explain exactly what systemic risk is.

Systemic risk is the possibility that an event within a specific company or group could cause massive instability and uncertainty across an entire market. In this case, we’re concerned with systemic risk within the market of cryptocurrencies and tokens. Companies or groups that are systemic risks are sometimes colloquially referred to as “too big to fail”, i.e. if it fails we’re FUBAR, so it can’t fail.

There are many different types of systemic risk, and it all really depends on the industry or field that we’re concerned with. A systemic risk in a particular market could be contained simply in that market, and could have no impact on the wider economy as a whole. Sometimes, systemic risk could cause instability in the entire economy. These are the ones we should be the most concerned about.

What’s particularly concerning about systemic risk is how often people are blind to it, most often unwillingly but sometimes willingly. But wait, why would somebody choose to be willingly blind towards risk? Wouldn’t investors want to be aware of it so they can take caution and take actions to prevent being affected by systemic risk? The answer, simply put, is no.

Cryptocurrency investors can too willingly ignore obvious systemic risk because they’re making too much money to be concerned with some stupid concept like “systemic risk”, because what in the world is “systemic risk” anyhow? Just another term that economics professors (whom they view as charlatans) use to prevent them from making more money with risky investments, in their view. To them, that’s somebody else’s problem to deal with, not theirs.

One of the difficulties of systemic risk is it’s nearly impossible to make exact predictions regarding whether or not it’ll actually affect anything, and how it’ll affect the market, unless one is privy to insider information. The more precise the prediction regarding systemic risk, the less likely it is to occur, and thus people try to avoid calling something a systemic risk to avoid looking like a fool if the supposed “systemic risk” that they declare never takes place. This is one reason, I believe, why the most alarming and obvious systemic risks are willingly ignored.

Let’s say I call something out as being an obvious systemic risk and make a big fuss out of it to everybody that I can so that they’re aware of it. Maybe, just maybe, I could be wrong and nothing bad materializes out of the systemic risk I kept yammering about. Now my reputation is ruined because I made such an uproar about something that, ultimately, was insignificant. Who wants that to happen to them? That’s often why people who point out the obvious systemic risks are the ones at the bottom of the totem pole: they have nothing to lose. If they’re wrong then it doesn’t affect them as much because they didn’t have a reputation in the first place. But if they’re right, they’ll have fame (or infamy) and most likely get book deals, be invited to CNBC, and maybe even be a main character in a biopic if they detect and call out systemic risk for something particularly important (e.g. The Big Short).

One aspect about systemic risk is the idea of the “Cassandra” archetype. What is this archetype? Cassandra was a woman in greek mythology who was cursed to speak true prophecies that nobody else believed. Cassandras exist to this day; these are the people calling out systemic risks in financial markets that people turn a blind-eye to. They’re viewed as obnoxious at best, and harmful at worst, and they’re not redeemed until their prophecies (i.e. systemic risks) materialize and cause catastrophe.

A difficulty that investors might have is distinguishing between the Cassandras of the financial market, and the delusional hucksters. So I’d like to propose some questions you can use when attempting to assess whether somebody is a harbinger of (mis)fortune, or completely deluded. Note that these questions aren’t exhaustive, but hopefully it provides a good jumping off point to allow you to generate your own questions/criteria. Note this doesn’t just apply to cryptocurrency, but almost anything. In any case, here are the questions you should be asking:

Questions to ask yourself to determine if somebody is a quack, charlatan, or con-artist

- Does this person have experience within this field?

- Has this person published any peer-reviewed papers/books on the subject?

- Has this person been accredited by a reputable organization as an expert in the field?

- Is this person knowledgeable of current literature and information in the field?

2. What is this person’s incentives?

- Are they ideologically motivated?

- Are they financially motivated?

- Do they have skin in the game (e.g. do they get affected if they’re wrong)?

3. How accurate is the information they’re using?

- Do they use facts/data to back up their arguments, or do they mostly use conjecture?

- Are the facts they’re using relevant to the claim they’re trying to make?

- Are the sources they provide reputable?

4. Who else is saying something similar?

- Are other reputable people saying the same thing?

- If so, how many people are saying it that are considered experts in their field?

5. How bad would it be to their reputation if they were wrong?

6. How adamant are they about their warnings to others?

In Conclusion

Be aware of systemic risks when you are investing in cryptocurrencies. Avoid excessive hubris, and stop telling yourself “this time it’s different” if the fundamentals of a cryptocurrency investment doesn’t make sense. When a so-called blockchain/cryptocurrency expert claims or predicts something, ask yourself the questions that I’ve provided above to figure out how much you should consider their opinion.

Best of luck with your cryptocurrency investments. May the investment fundamentals be in your favor.

On the sources of systemic risk in cryptocurrency markets

Nassim Taleb coined the term “anti-fragile” to describe systems that benefit from shocks. Crypto economic systems may display fragile, robust, and anti-fragile characteristics.

Summary

Value in algorithmic currencies resides literally in the information content of the calculations; but given the constraints of consensus (security drivers) and the necessity for network effects (economic drivers), the definition of value extends to the multilayered structure of the network itself — that is, to the information content of the topology of the nodes in the blockchain network, and, on the complexity of the economic activity in the peripheral networks of the web, mobile apps, mesh-IoT networks, and so on. In this boundary between the information flows of the native network that serves as the substrate to the blockchain, and that of the real-world data, is where a new “fragility vector” emerges. Our research question is whether factors related to market structure and design, transaction and timing cost, price formation and price discovery, information and disclosure, and market maker and investor behavior, are quantifiable to the degree that can be used to price risk in digital asset markets. We use an adaptive artificial intelligence method to study the adaptive system of crypto currency markets. The results obtained show that while in the popular discourse blockchains are considered robust and cryptocurrencies anti-fragile, the cryptocurrency markets may display fragile features.

Intro

There have been numerous cases documented of malfunctions in the cryptocurrency markets; some have been related to the internal operation of exchanges, such as the glitch in the cryptocurrency exchange GDAX that crashed the price of Ether from $319 to 10 cents (Kharpal); others have to do with the dissemination of information, such as the negative impact on bitcoin prices after the de-listing of Korean exchanges in Coinmarketcap, a popular price tracker (Morris).

While the bitcoin network is decentralized by design, the web and other peripheral networks where the services that enable the bitcoin economy operate are not. This extends to any other cryptocurrencies with a sufficiently high degree of decentralization, such as Ether. Roll (ROLL 1984) demonstrated that volatility is affected by market microstructure, and by applying this idea to the off-chain side of a crypto-economy we are able to develop real-life risk metrics for the blockchain financial system.

Identifying systemically important services in cryptocurrency markets

At the time of writing, March 6th 2018, 3:38 PM (UTC), the total market capitalization of the cryptocurrency markets (including coins, excluding tokens) was $405,939,039,748. The largest assets by capitalization are bitcoin (BTC) $187,065,686,782, and ether (ETH) $81,602,911,777.

To begin the development of an analytical model which is behavioral finance-aware, we should consider that in the retail segment, people usually utilize one or more public services before checking the status of, or performing a transaction. Those services include price trackers targeted at different regional markets, trading platforms of various types, centralized exchanges and instant exchanges, wallets, among many others. We use a common usage metric; a sample of the largest 1000 contributors to the Bitcoin network and 1000 contributors to the Ethereum network (measured at points of consumption) are shown in Figure 1.

Given the different use case of each crypto asset, each tends to have a number of specialized services around its orbit. However, many others are shared (with a higher density at the BTC side, top left). If we start mapping the relationships between services as well, the problem will quickly become intractable.

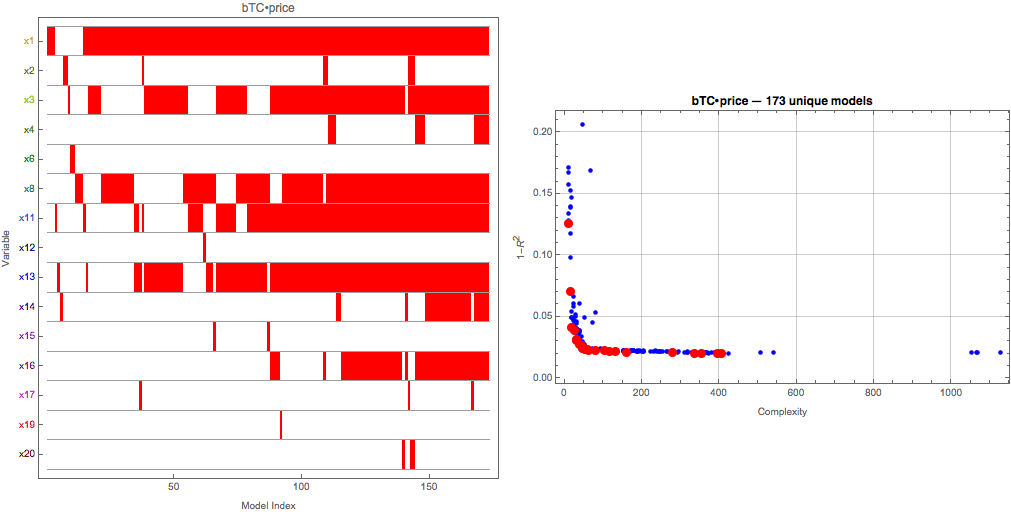

The common sources in both sets bring the variables of interest from 1000 to 196, so we can further prioritize sources by traffic contribution. But ultimately we use an adaptive approach as a way to detect invariance, and capture general relationships by using prices are the response variables. This treatment of the data reduces the variable set to 22 (see Figure 2). The adaptive approach produces models that compete to reduce the error while maintaining the lowest degree of complexity. In the accuracy-complexity Pareto of the figure, optimal models (with the best possible trade-off) are depicted by red points. We also note, by the variable presence across models, that only a handful of sources are of material importance.

Systemic risk mapping

It is possible to study multivariate volatility using traditional methods, but let us take advantage of the expressions generated to construct a graph representation of system dependencies.

Detection of (Anti) Fragility

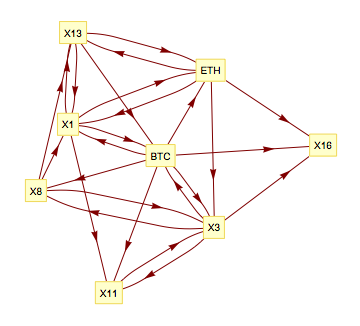

Formally, fragility and antifragility are defined as negative or positive sensitivity to a semi-measure of dispersion and volatility (Taleb 2013). What is different in this case is that we are not concerned with exposure to price shocks only, but prices themselves can change abruptly in response to events from the environment. By constructing a graph using formulas selected from our adaptive exploration of the model space we obtain a network as the one in Figure 3.

The network reveals the sources of fragility, overlapping exposures, and, relevant feedback effects. For instance, it becomes clear than Ether prices are affected by changes in BTC prices and not the other way around. It also can be understood what are the shared risk drivers (e.g. the usage of X1 has an effect on both BTC and ETH), which allows for more control over aggregate factor exposure (in hedge fund speak).

This approach also allows uncovering secondary effects. A bet on X11 and X3 may prove ineffective since those have a relationship of mutual dependence — but their risk profiles are different since X3 is exposed to both crypto asset prices directly; they also affect the environment differently — X3 has a higher outdegree than X11 (more outgoing connections). In this particular case this makes sense: in practice, a wallet service will be more affected by activity in selected exchanges, than directly by prices.

Finally, the method makes tractable the nodes of systemic importance, e.g. X1, X3, and X13, all have a relationship with bitcoin prices. This is something that would be impossible to find in a traditional network representation such as Figure 1.

Regulatory and Cyber risk

The risk network also offers an opportunity to disambiguate opaque situations. For instance, X13 appears to portrait a spurious relationship (how can a service affect the price of a decentralized currency?), but a closer inspection reveals the occurrence of a extreme/tail event. After the crackdown of the Chinese government on bitcoin exchanges in September of 2017, one of the most popular exchanges rebranded and initiated operations as an international service (but still, being accessed mainly from mainland China). As we can see in Figure 6, the remarkable growth in what would be an impossible timeframe for most online services (several orders of magnitude in less than 6 months) not only explains the behavior captured by the model, but provides evidence of the increase on the survival rate of systemically important nodes in the crypto economy. Some services prove hard to kill, even if they operate in the centralized part of the economy. In this sense, those components enhance the anti-fragile characteristics — they simultaneously boost the underlying, and may even benefit from the shocks.

No comments:

Post a Comment